Pantry and Palate | Simon Thibault

Pantry and Palate

Remembering And Rediscovering Acadian Food

By Simon Thibault

Photos by Noah Fecks

Suzy Chase: Welcome to the Cookery By The Book podcast, with me, Suzy Chase.

Simon: Hi, I'm Simon Thibault, and my new cookbook is called, "Pantry and Palate: Remembering and Rediscovering Acadian Food."

Suzy Chase: I adore cookbooks like this, it's more than just a cookbook, it's a family narrative that spans over 100 years. A reacquaintance with old food traditions, with recipes, and anecdotes, seasoned with history. Acadie doesn't exist geographically anymore, so what exactly defines the Acadians?

Simon: Acadie is defined by the people, and it's defined by family more than anything else. One of the first things that happens when you're in Acadian communities, is people will ask you, "Well, who are your parents?" That way, you can start to establish a possible family connection. Like mine would be, I am Simon, son of Hector, son of Ulysses, son of William, son of Isadore. Within those five generations, you and I might be able to find some kind of familial connection, and that's how Acadians identify themselves. We're always in this constant state of seeking each other out, that's how we exist.

Suzy Chase: The connection between the Cajuns, and the Acadians intrigued me, talk a little bit about that.

Simon: Sure, I mean historically what you essentially have, is that in 1755, the Acadians were colonists to what is now Atlantic Canada, specifically New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, and actually into parts of what is now Maine, actually. We were there, and we were colonists to the area, and then the English were like, "Uh, sign fealty to the crown, or we're kicking you out, because we're afraid of you being still French," and we're like, "No, we're not French, we don't care."

They kicked us out, and we were sent all over the place, some of us went back to France, and some people who went back to France later on ended up in Louisiana, and the best example of describing the connection between Acadians and Cajuns. It was a gentleman named Barry Ancelet. Barry is very much like a very militant Cajun, he's a poet, and musician, professor at Lafayette, and he once said that it's like talking to two siblings who were separated the age of eight, and meet again when their 80.

You have a root, but you have a completely different life experience, and then you meet again, but you still feel this strong kinship. I have a lot of friends from Nova Scotia, and from my New Brunswick, who have gone to Louisiana, and as soon as you say you're Acadian, it's like, "Come unto my house my cousin, we're going to go eat together." There's this really wonderful connection, and again that desire to reconnect that kind of exists.

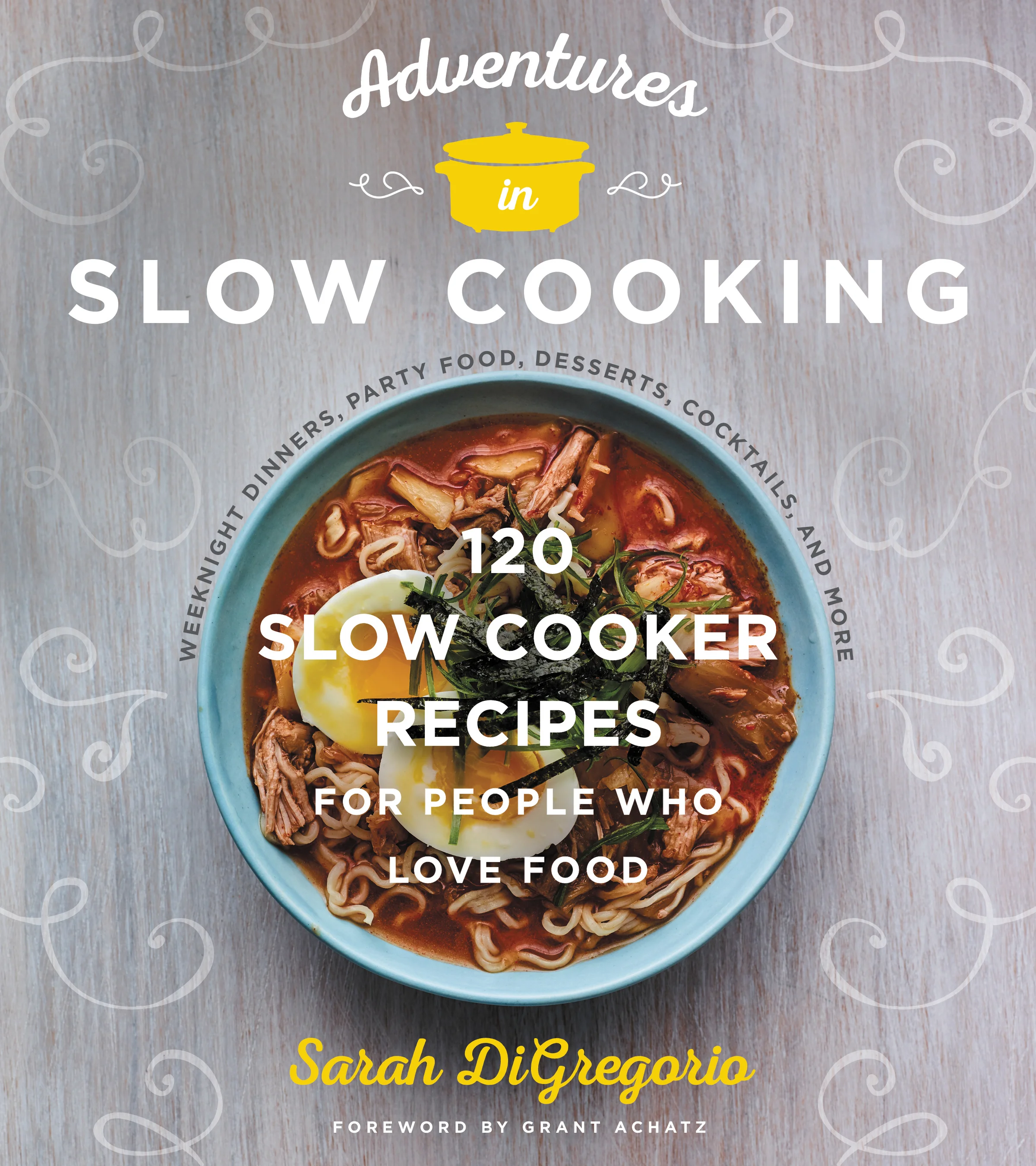

Suzy Chase: I'm with you, I don't want a cook that teaches you how to dump and stir.

Simon: Thank you.

Suzy Chase: I want a culture, and cuisine mixed into my cookbooks, so when you were doing the research, you said that there was only one Acadian cookbook published in 1974 that was in French, is that right?

Simon: Yeah, pretty much, and that book wasn't even translated into English until like 2001. It's funny, I know a friend of mine works for the publisher who published that book, and she said, "Your book has actually helped our book sell again." Which is great, the more the merrier really, but yeah, there was very little information, and so it was very much a question of going through primary sources, but luckily the primary source for my book were a series of notebooks, which were my grandmother's, and my mother's, and my great aunts, and various other family members.

When I first started this book, because there was no other real ... Other than the one cookbook around this, it was very difficult to decide what to put in, and my background is in journalism, so it's very much a question of, how far back do you go? How far do you start digging? Then I started looking into everything from like agricultural reports, to folklore, to everywhere, and I was like, "Oh my God, what am I going to do?" This woman, who is kind of a mentor of mine, Naomi Duguid, she's a James Beard award-winning author.

She, and her ex husband wrote a series of cookbooks, two of which won book of the year award, and she lives in Toronto here in Canada, and she and I were talking, and she said, "Just write the recipes, don't worry about all the information you think you're missing. The recipes will tell you where to focus," and she was right, and I decided to focus on these family recipes, but the family recipe, again with the whole thing of being Acadian, your family will tell you who you are, and where to go, and where to seek out things like further back, and that was the key to it all, and I'm really grateful for that.

The recipes taught me where to dig, so a simple recipe of a cornmeal molasses bread can lead me back to how the Acadians came in contact with the loyalists, who were Americans who had left the United States after the War of Independence, and how those traditions became part of it. Within the loyalists, there are also black loyalists, so African Nova Scotian communities were in conjunction with all of these things, or like the tradition of rasping potatoes, and using that pulp in a very specific way, that's German influence, that's a German thing.

The Acadians didn't do that realistically beforehand, so each recipe told me where to go, and so it was a heck of a research project, but the best part about it all for me, was that doing all this research, and cooking, was about experiencing what it means to be Acadian in a context that I had never experienced before, and not in such a profound way, and so I'm really grateful for that.

Suzy Chase: Going through the series of notebooks that your mother gave you, did you discover something you never knew about your mom, or your grandma?

Simon: I really did, because the thing was, that my grandmother who wrote the majority of these notebooks, she passed away when I was like four, or five, so I never really knew her. I only know her through story, through like stories that my mother would tell about her, or that my uncle would say about her, so I had no real connection to this woman, not in the same way that I had to other grandparents, or whatnot, or other family members.

In digging through this, I came to understand who she was, and what her life was like on a daily basis, and that was not only a wonderful educational process, but a wonderful process that I came to understand who this woman was for my own mother, and that was a connection that I never would've had beforehand, and so I'm again deeply grateful for that. More than anything, it was also interesting to see the life that she had. You have a woman who graduated high school when she was 16, but because she couldn't go to teachers college education yet, because she had to be 18, her brother, who was a priest, sent her to a finishing school in Québec for the Ursuline College, which actually was the first college established for women in North America.

She went there for two years, and so she learned what was then known as les arts menagers, or home economics, but not home economics where like what would've been for you, or myself, meaning like how to do very simple things. It's like no, economics in all of this, what is the nutritive value of certain forms of food? What is the price of these things? How can I stretch that? How can I cook these things? All of these things, like how to truly create a home, and as I was digging through all of this, and realizing there were very simple, and subtle things that my mother did, that I was like, "Oh, that's the root of the that," which was kind of wonderful to see.

Suzy Chase: When was your grandmother born?

Simon: She was born in 1908, or in '09 if I remember correctly. The books were also written by my grandmother, and also other ancestors like a Great Aunt, and things like that, so you have everything from the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s, and 60s in all of this, so you see everything from the development of industrialization, industrialized foods. You will see recipes like some things will ask for baking soda, but it will actually ask for what they would call Pearl Ash, which technically is actually baking soda.

Later recipes will ask for baking powder, so you see the development of things in the 20th century, and whatnot, which was super interesting to me.

Suzy Chase: The gorgeous cursive that we don't see anymore.

Simon: Oh God yes. It's fun, I've seen enough of it now that I'm like, "You were taught by nuns, you were taught by nuns," you can just tell by the writing.

Suzy Chase: With so many recipes handed down from generation to generation, the measurements are vague. What was the recipe testing like for you?

Simon: I'm not a professional cook, I never went to culinary school. I'm a journalist, so my background in all of this, and I'm very much a self taught cook, but because of my background in journalism, my interest is always as thorough as possible, and I'm the kind of guy who will go and try anything once, especially in terms of cookery, and testing out in techniques, and whatnot. I realized that it's one thing for me to be able to cook on my own, it's another thing for me to transmit that information to another person, and for them to be able to execute it, that was the job.

Like you said, all of these recipes, the vast majority of them had next to no directions, and relatively vague measurements. I would fiddle around, figure it out. I was really lucky, because I have a friend who works at America's Test Kitchen, he works for Cook's Country's. His name is Tucker Shaw, super sweet guy, and I emailed him, and I said, "Tucker, what am I going to do about how to transmit this information?" He gave me a bunch of really great tips, and one of which, was read the recipe out loud, or get someone actually, no, get someone to read you the recipe out loud, close your eyes, and mime with your hands what you think should be doing.

Suzy Chase: Really?

Simon: Yeah, but it's true, because if you've cooked enough, or you've baked enough, you should know intrinsically when things should happen, and if someone's telling you what to do, and all of a sudden your brain goes, "No, I shouldn't be doing that yet," it makes sense, you know what I mean?

Suzy Chase: Yes.

Simon: Yeah, it was a really smart tip, so thank you Tucker Shaw.

Suzy Chase: Why can't you find Acadian food in restaurants?

Simon: For various reasons. The number one thing is most people just cook it at home. It's most of the major dishes tends to be large family gathering kind of dishes, that's one thing, but if you are in Acadian communities, you will occasionally find it on a few things, like occasionally in diners, and things like that. The thing is, because Acadians lived a form of life that was often subsistence cookery, survival, peasant food, food that would stick to your ribs, and keep going through a long day of work, there is next to no refinement as we view refinement today.

The idea of something being necessarily aesthetically pleasing on a plate as we view it today in the 21st century, doesn't really stick around. I've often said that Acadian food is homey, and homely, but very pleasing to the stomach. It's more pleasing to the stomach than to the eye. A perfect example is this dish called Rapure, or Rappie Pie, which is a dish of you take potatoes, you rasp the potatoes, and then you extrude all of the starch out of them by squeezing them, and then you reconstitute that with stock, and that creates this ...

Suzy Chase: Porridge?

Simon: Yeah, it's like a potato porridge, or a potato congee, or jook, and it's just kind of like, "Okay," and then you add some form of meat to it, whether it be poultry, or wild game, or even like clams, like large bar clams, which is a favorite of mine, and then you bake that in an oven at God like 400, 450°, I can't remember right off the top of my head right now, but like for an extended period of time, and it's basically insanely thick, mildly gelatinous, and sits on your plate, but it sits in your belly, and you're just like, "I am so full of food right now, and so happy," and think about it, it will keep you going for a long time, but it's not the sexiest thing in the world.

I recently was lucky enough to have the chance to hang out with some people from the perennial plate, who were this lovely couple from Minnesota who've won multiple Beard Awards for their videos, and I took them around, and there's a shot in the short that we did where you see someone plating Rappie Pie on a plate, and you just this sound as it hits the plate, and it jiggles, and then, "Yep, that's it." I know a lot of people would just be going, "What am I eating? What?" It's kind of fun like that, but I mean I don't know, I love it, and I grew up on it.

It's like everybody, I think if you have any form of ... No matter what your ethnicity, there's oftentimes some kind of dish somewhere that it's like, "This is just for us, it's not for you." It's always fun when someone who is not from your community comes in, and really adores it, it's like, "Okay, you can stick around."

Suzy Chase: On Monday night I made your recipe for Cajun Fricot, and that's not a looker either.

Simon: No, it's not, but ...

Suzy Chase: It's so darn good.

Simon: Good, good.

Suzy Chase: I had my brand-new class parent committee over for dinner, and they loved it, and the spicy Cajun sausage really flavored the chicken, which was interesting.

Simon: Yeah, totally, so Fricot is basically a chicken and dumplings stew, you'll find it throughout most Acadian communities, if not all of them, but in the 1990s, a bunch of people from Louisiana started coming to Southwestern Nova Scotia, which is where I grew up in a little village called Church Point, or Pointe-De-L'Eglise. In this village there is actually a university, it's called Universite Sainte-Anne, or University Sainte-Anne, and at Sainte-Anne there is an immersion program.

French immersion, so people will come in, and learn how to speak French, and a lot of people in the 1990s started coming there to learn French, because they wanted to reaffirm their cultural heritage through a linguistic way. A lot of people from Louisiana came up, and they were like, "All right, well, let's try some of your dishes," and they all went, "Oh, you all need spice in this. Where's the pepper, where's the seasoning, where's the spice," and we're like, "No, not there."

One gentleman, a really wonderful guy named Lucius Fontino, who everybody told me, "You need to talk to Lucius," like for years, and so Lucius and I finally started talking, and he said he had gone down, and he'd had it, and he was like, "This would be really good with sausage, or just spice it up," and so when he went back to Louisiana, he started making Fricot, but he made it with a little bit of pepper, or a little bit of Tasso Ham, or Cajun sausage. Most people outside of the South can't get Tasso, so I was like alright, any kind of like decently nice Cajun spicy sausage will do well in a pinch, and it's funny, it's one of the recipes that has gotten a lot of attention, from a lot of people, which is kind of wonderful.

Suzy Chase: I encourage everyone to make it, it's on page 125.

Simon: Thank you.

Suzy Chase: You scoured through old cookbooks, and recipes, and said that the feedback you received from other Acadian families has been eye-opening, how so.

Simon: One of things, is as an Acadian, because there's been so little attention to our food, and all of a sudden my book comes out, and people are like, "Oh, we can talk about this?" This is now a point of pride for people, because amongst Cajuns, the way that you express yourself, is by your food, but Acadians express themselves by what comes out of their mouths, the way that they speak, but for Cajuns, it's what goes in your mouth. All of a sudden there's this new way to express Acadian pride, and the sense of who we are.

Food is a cultural product, or a cultural artifact, whichever way you want to view it, and all of a sudden for people to like, "Oh, we can talk about this, we can be proud about this," and people are interested in it. That's been the thing, but the other thing of it, is that some people have been like, "Well, why did you do it like this?" It is such a food of people's homes, and no matter what your ethnicity is, the food of your cultural heritage is always very indicative of your own family, and so some people were like, "Well, why did you not do this? Why did you do it this way?"

In the Fricot, like the classic Fricot, I had some people who were like, "What are you doing? Why do you have carrots in your Fricot?" I was like, "Oh, come on, like my mother doesn't do it," but I was like I need to give people some form of introduction to this, and I even say, I was like, "Carrots are not habitual, it's okay," like you have to think of what's the easiest point of access for people who have no context of this food to get into it.

I even had one person completely, and utterly criticize me. They were like, "He said it's going to be all his grandmothers recipes, but he's all bastardized them." I'm like, "I haven't bastardized anything, I've basically made sense of it." No, it's been super fun, like I mean I live in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I work as a freelance journalist, and when I wrote this book, I thought, "Okay, it'll do well in Atlantic Canada, and maybe a few other things."

It gained national attention here in Canada, it was on the cover of the life section of the biggest newspaper in the country. I've done interviews all over the place, and now it's getting interest in the US, which is kind of amazing, and I mean that was the point, is to get people talking about this. It wasn't purely from an intellectual point of view, or from an educational point of view. Acadians live all over the place, most of us are based here in Atlantic Canada, or in parts of Québec, and a little bit of Maine, but we are a diasporic people, we are a diaspora.

We are living all over the place, and we very specific, and individualistic kind of experiences of what it means to be Acadian, and to see that in the media it resented, there was so many people like, "Oh my God, we're here, we're being viewed, we're being talked about." It was kind of wonderful for people, and it's a little surreal, all of a sudden I've become this accidental Acadian spokesperson. I'm like, "I didn't sign up for this, I'm happy to do it, but it's that's not what I expected to happen."

Suzy Chase: Is your mother still alive?

Simon: Yeah, both my parents are very happy, and healthy, knock on wood, as I'm knocking on my head.

Suzy Chase: Are they so proud of you?

Simon: Yeah, they're very, they're just like, they can't get over it, like just how many people have come up to them, and just people will come up to my mom, and be like, even people have told me they remember my grandmother, or told my mother that they remember her mother. Like one gentleman, we had a book launch down home for the book, it was in the month of May, and this gentleman came up, and he said to me, "I remember your grandmother's cooking, I remember sitting at your grandmother's table with your mother when she was a child, and just eating these foods," and it was kind of amazing.

He just had tears in his eyes, he was like, "I haven't thought of these flavors of these things for years," so it was kind of amazing, but no. It's funny, because my parents are relatively private people in the sense of they will talk to everybody, but they've never been people to seek out a new form of notoriety, or fame, or anything else, and people are stopping them in the street, and they're like, "I read your son's book," and like oh my God, it's resonating in lots of places, so it's been wonderful for them.

Suzy Chase: A recent entry on your blog called Cookbook Love described your love of cookbooks, and the first time you walked into Kitchen Arts & Letters here in New York City, recount that moment for us.

Simon: It was April of 2015, I was in New York for the James Beard awards. I was going to the award ceremony, and friends of mine are like, "You have to go to Kitchen Arts," and I read cookbooks like their novels, I read them cover to cover, and I walked in, and I met Nach, who is one of the major owners of the store, and one of his other staff members, and he was talking to a woman, she was looking for a book on Chinese cookery, and he mentioned Fuchsia Dunlop, who is one of my favorite cookery writers.

She's a British woman, who has made an entire career talking about Chinese cookery, and he was talking about her books, and I just said to the woman, "If you don't mind me interrupting," I said, "You should really read her book, Sharks Fin and Sichuan Pepper, because chapter 4 is specifically about the appreciation, and the understanding of texture in Chinese cuisine." Nach looks at me, he's like, "Do you want a job here? I just kind of hit the floor. I was like, "I seriously would if I lived in New York, I would apply for there in a heartbeat."

Nach and I just started talking, and he gave me a bunch of really wonderful suggestions. I said, "These are the kinds of things that I read," but it was just amazing to be in a store that is so dedicated to cookery, and every single form from intellectualization, to the practicality, to the aesthetic, and the staffers were just so knowledgeable, and so accommodating, and knew so much about what there was in the store, it was kind of amazing, and I left there with having spent, I don't know, $400, $500.

I got to the airport, and my luggage was overweight. The guy at the counter is like, "That will be $100 please." I'm like, "Ah, shit."

Suzy Chase: It's money, that's all.

Simon: Just money, but I've fallen in love with that store, and every time I go to New York I made a point of going, and then when the book came out, one of the other owners, Matt said to me, he said, "We could do a book launch here," and I was really amazed, and I said, "Yes, please." In November this year I went down to New York again, and we had a small little book launch, and a few friends of mine showed up, which was really lovely, and then the event was over, and two things happen.

One, I was just about to leave, and Matt said, "Can you please sign some copies for us," and I said, "Sure." I said, "How many do you want me to sign? If you don't sell them, you can always send them back." Matt says, "Oh no, I'm going to sell them all."

Suzy Chase: Wow.

Simon: I was a little taken aback, and I was just really moved, because this is a store that is pretty much the Platonic ideal of what my interesting food is. Like I said, there is an intellectualization, there's a practicality to it, but it's all about getting people to cook, and to think about food, and I think that's really amazing. After I signed the copies, the nights over, I walk out, and I'm with a friend of mine, and I just burst into tears. He's like, "What's wrong?" I'm like, "Nothings wrong, I just had a book launch in New York."

Suzy Chase: You made it.

Simon: Yeah, it was really kind of amazing, and I was really, really pleased. Just in December of this year, Kitchen Arts & Letters put out their list of the top 10 cookbooks of the year, and there was my book.

Suzy Chase: Yep.

Simon: I was like, all right, I don't need anything else anymore, I'm good, like to me that was the be-all, and end-all.

Suzy Chase: It was one of their favorites for 2017.

Simon: Yeah, so I'm sitting there on the list sitting next to Wylie Dufresne, and it's like are you kidding me? David Tanis, and all these people, I'm like, this is insane. I remember my first time in New York, I came, and I was at the Beard Awards, and I'm sitting at this table, and I'm looking around, and Dan Barber's the table next to mine, the Kitchen Sisters are two tables over. Dorie Greenspan is up on stage, and I'm like, "Where am I?" I just sat next to this woman, and I said to her, and I said, "I'm sorry, I just feel like a little bit of a country mouse, and I don't know what to do," and she said, "That's okay, I don't know, I understand that feeling completely."

She was there with her son, and she was from Colorado, she's like, "Mom, you have one of these." She's like, "Yeah, but I still feel like a country mouse." I was like, "It's okay, it's okay to have those kinds of moments," and especially, like I said, I live in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I love where I live, but it's one thing to see what you're doing as a professional, and then finally get the recognition, and just have it happen it that kind of way has been incredibly, it's been liberating, but it's inspiring, but more than anything, it's shown me that I can do what I need to do, I can do this. There's this is affirmation that has come about, that I'm like, "No, I'm doing the right thing, and it's good.

Suzy Chase: You also love Bonnie Slotnick too.

Simon: Oh my God.

Suzy Chase: Do you want to hear the craziest story?

Simon: Please.

Suzy Chase: We moved to 10th St. here in the West Village, and I said, "I'm so excited, I'm going to be a couple blocks away from Bonnie Slotnick." That same month we moved in, she moved out over to the East Village. I was so upset. Anyways, she's still close.

Simon: Yeah, I mean, and she's the sweetest woman ever. Two people I know who live here in Halifax, are originally from New York, and they're living here now, but they'd asked her for a book 10 years ago, and about two years ago they got a phone call, "Are you still looking for this book?" They were like, "Yes." She remembered them eight years later, even thought they weren't living in New York anymore. I mean ...

Suzy Chase: That's incredible.

Simon: Bonnie is a walking repository of culinary information around books that is like unparalleled, it's insane, and amazing, and every time ... I have friends who go to New York, I'm like, "Two places to go, Kitchen Arts & Letters, and Bonnie Slotnick," and just sit in Bonnie's, and just look for the most random things. I mean I found a first edition of a cookbook from Nova Scotia in there. I found all kinds of wonderful goodies in there, and I can ask her about things, and I actually met a real hero of mine in Bonnie Slotnick.

I met Grace Young, who is an award-winning author who wrote a really wonderful book called, "The Breath of the Walk." I was in there one day, I was on a trip to New York, and I left, and about five minutes later she walked in, so I had missed her, and I had been talking to Bonnie about how much I loved her books, and she said, "Well, she's in here often," and so I got in contact with Grace, and I actually got to meet Grace at Bonnie Slotnick, and I said, "All right, we're going to go to the Chinese cookery section, and you're going to tell me what are the books that I need to own." It was a pretty amazing experience.

Suzy Chase: That's surreal.

Simon: Yeah, it was wonderful, but that's the wonderful thing about, we live in a celebrity culture, and yes, food people have deservedly garnered attention for the work that they do, whether it be working in kitchens, or writing about food, but there's still a highly democratic ... It's still a very democratic way of living, and working, meaning that you can often contact these people, and they often will help you.

I think that's a really important thing, and a really important thing to emulate in your own behavior, is like if there's all this information out there, why would you keep it to yourself? Share the knowledge, that's the whole point of cookery, is to share that knowledge in as many ways as possible. That's been amazing, and this kind of work that I've been doing around working in food journalism, is that grossly, the majority of people will be like, "No, I want you to have this information, and I want to help one another, and it's like, let's just get people cooking, let's get people thinking about food. Let's give people agency to do what they need to do," and that's really wonderful.

Suzy Chase: Where can we find you on the web and social media?

Simon: Yeah, you can find work at simonthibault.com, I'm also on Twitter, and Instagram. That's SimonAThibault, and Thibault is spelled T-H-I, B as in Bobby, A-U-L-T, and you can actually recently find me, if you go to Perennial Plates website. Perennial Plate recently did a video where I explained to them what Acadian food is, and took them down to where I grew up, and had some Acadian food with the gang from Perennial, and it's a really wonderful video.

Suzy Chase: You've said cookbooks have allowed you to travel the world, and now you've allowed us to travel through your terrific new cookbook. Thanks Simon for coming on Cookery By The Book podcast.

Simon: Thank you so much for having me, it's been wonderful.

Suzy Chase: Follow me on Instagram at CookeryByTheBook, Twitter is IAmSuzyChase, and download your Kitchen Mix Tapes, music to cook by on Spotify at Cookery By The Book. As always, subscribe in Apple Podcasts.