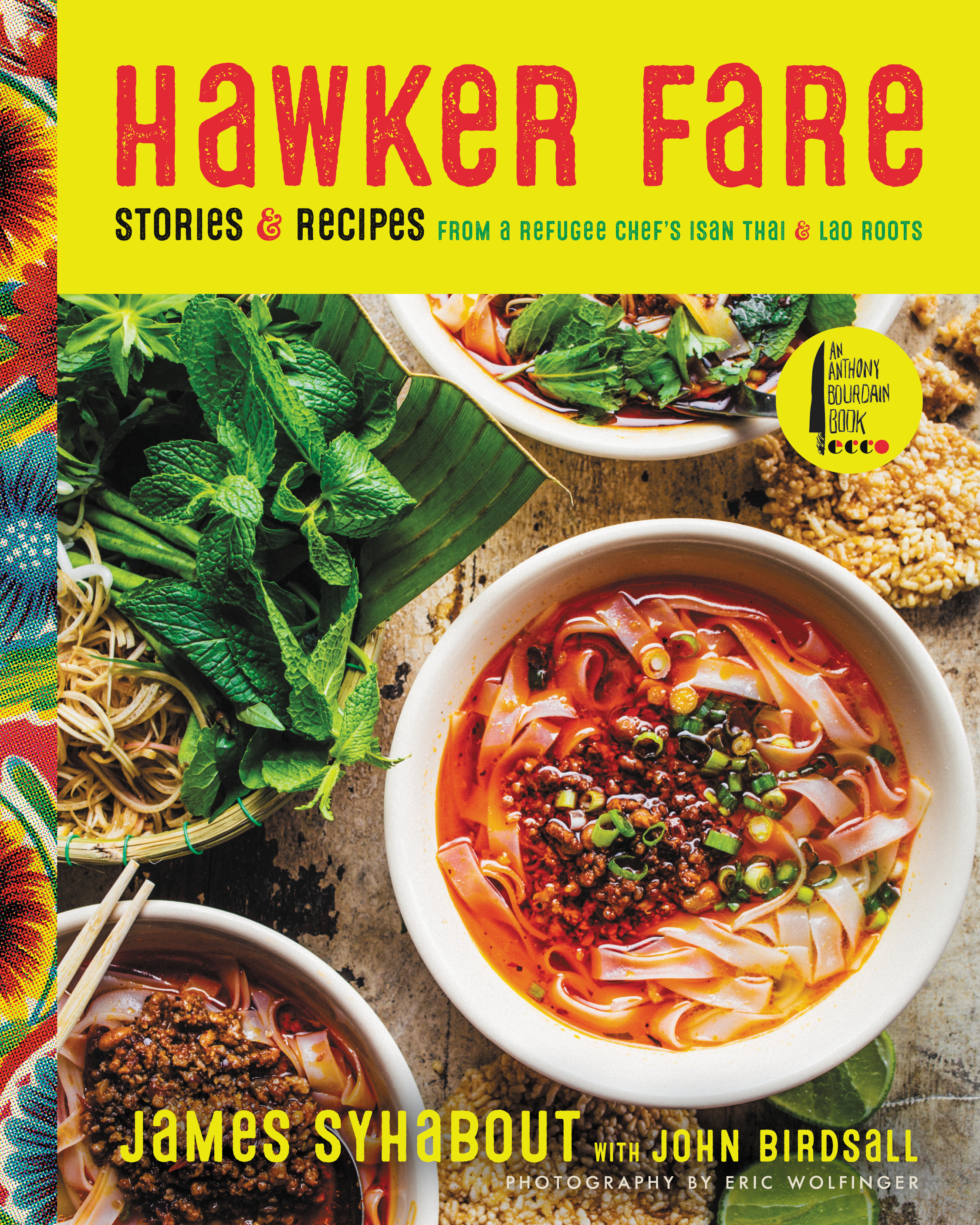

Hawker Fare | James Syhabout

Hawker Fare

Stories & Recipes From A Refugee Chef's Isan Thai & Lao Roots

By James Syhabout

with John Birdsall

Suzy Chase: Welcome to the Cookery by the Book podcast, with me Suzy Chase.

James: Hello, my name is James Syhabout and my latest cookbook is Hawker Fare, stories and recipes from a Thai and Laos chef's refugee's point of view.

Suzy Chase: In the preface of Hawker Fare, Anthony Bourdain wrote "This book will make you a better person. That's before you even try any of the recipes."

Wow! What a ringing endorsement.

So let's kick things off with a bit of geography lesson. Where is Laos and what defines the cuisine?

James: Laos is a land locked country wedged in the North East of Thailand, between Thailand and Vietnam with Cambodia kind of like adjacent to it.

Being a land lock country, you know there's a lot of preservation involved. Like fish sauce, and stuff. Unfiltered style fish sauce called Padaek. So that's kind of like the basis of seasoning in Laos food that can be funky. It can be like anchovy deliciousness, and spice levels, you know a lot of dried chilies.

Also it's very, cause it's land lock, jungle you know? So things are very herbacious, bitter, that's kind of like ... and also like seafood, but like fresh water. The only body of water we have is the Mekong river running through the country.

Suzy Chase: The first hundred and twenty five pages in this book detail your family's journey. Take us back to 1981 when you and your folks arrived in Oakland as refugees.

James: That year when we arrived, couple of suitcases, there wasn't much else too at the time. We arrived in Alameda, which is a small island right across the estuary from Oakland. We stay over there for like a week until our social worker found us permanent stay. We ended up in Oakland on 25th and telegraph with a bunch of other fellow Laos families that pretty much had the same kind of story, just mainly coming from different parts of Laos.

There were some people coming from Vientiane, some people from Luang Prabang, some people from Nong Khiaw, and that's how we settled and that's how the story became, and that was our little Laos community. The little Laos hub, just one block, small block radius.

Suzy Chase: So I read that Syhabout was the name given to your father by an immigration officer. What is your family name?

James: You know that's something I still can't get an answer, actually.

Suzy Chase: Really?

James: I know my mom's maiden name is Yeu Ying. I never had that conversation with my dad actually, my parents were separated so I never had that conversation. How did we derive this name, I goggled it. There's not so many Syhabouts out there.

Suzy Chase: Yeah.

James: So then the few Syhabouts that reached out to me are like "Are we related?" Uh, I'm not sure, maybe the last name but the last name is kind of made up. That's what my cousins were telling me. I'm like, okay then what is our real last name? It's like no one knows, it's kind of like this cool mystery like John Doe in a way.

Suzy Chase: Yeah.

James: But you know, I'm eager to find out actually now. But no, I kind of like the mysterious of it. I think the name is so unique I don't know how it got derived. Yeah, it's still a mystery that's unsolved. I think I'm going to leave it that way, I think it's much cooler.

Suzy Chase: So there's Lao, Laos, Laotian, Lao Isan? Can you explain those?

James: Yeah, the best person to explain this is Professor Vinya Sysamouth who I interviewed in the book, you know what's the difference is.

So the difference in Lao, Laos, Laotian. Isan is a region what we call in Thailand, that's Northeast, which was not part of the Lan Xang Kingdom, which is part of Laos. So culturally the Isan region of Thailand is culturally Lao. And Lao is Laos currently, and back then it was made up ... it was the most ethnically divers country in the world. There's forty plus ethnic groups and tribes and they all have their own dialects and different languages.

But you know we all related because that's the genetic make up of Laos. There's the Khmer, the Hmong, there's so many I can't name them all. But that's what Laos is.

I think about it's almost like California. What does it mean to say you're Californian? You can be from Mexico, from Laos, you could be from ... so when people say, I'm Khmer or Hmong their like, yeah you're Lao. You're from Laos, you're hill tribe. It's just very interesting place, I like to describe it like the bath country. It's wedged between France and Spain, but people know it as the bath country. And I feel like Isan is kind of the same way.

Suzy Chase: I can't even imagine what your parents went through in terms of culture shock when they moved to Oakland. I mean, everyday things like riding the bus or going to the grocery store must have been such a strange experience. Optimism kept them going, tell us about the restaurant that you parents opened.

James: The restaurant was your stereotypical mom-and-pop restaurant you know? It was family ran, family owned, from Uncles and Aunts and the kids in the front of the house. We would have purveyors so we would go down to China town and produce terminals and with a wad a cash and buy ingredients for the day or couple days. And that was kind of like the grind, that was the restaurant life.

Yeah it's definitely new seeing the lights and billboards and tall buildings. Where we came from the countryside, where we had dirt roads and water buffaloes and it's much ... very 180 degrees. Yeah, it's totally opposite. I don't know how we ended up in Oakland but I'm pretty sure my parents never seen a map or world globe before we came here.

But I think they rerolled the dice on optimism. I'm pretty sure they heard of America back then. It's like the land of opportunity, so yeah they kind of like rolled the dice and made a gamble of it.

Suzy Chase: So you helped out at the restaurant after school and on the weekends?

James: Yeah, it was like I said a true family restaurant, on the weekends. Afterschool I would catch a bus to the restaurant. My summers were spent at the restaurant in Concord. So I was never in town for that. I was like the prep cook, that was where my mom multi tasked, she had to babysit and run a business and cook and provide for us. So it was the only resources we had. We didn't have any other family in Oakland at that time, so had the self sufficient in a way.

Suzy Chase: Was that when you figured out you wanted to be a chef?

James: I figured out at a very early age that I wanted to be a chef. There's something about cooking that was very, very stimulating to me. And it kept my interest. I like doing it, I like food, I love ... which you know. I think there's a lot of seven, eight year old boys who would love to run around with a knife and play with fire. So, I just love eating, I eat everything. Something’s I wasn't allowed to eat. I wanted to try it, I would sneak it in. Raw beef larb, and they were like "You're too young to eat raw beef." I wanted to try it anyways, maybe because I was a vigilante. Kids don't like to do the things your mom tells you not to eat.

But I liked it, I liked those bitter flavors. I kind of took interest, it was like a whole new world that was different than what I was getting in public elementary school. School lunches like frozen pizza and corn dogs. Which meals were not exciting and kind of bland and boring. That's what kind of sparked my interest, and just being like the noise and sounds of a busy restaurant. It was just like overwhelming but it was like kept my interest and definitely kept my curiosities high. And that's how I got to love cooking. It's like every day is a new day. You know, I just felt alive.

Suzy Chase: When I started reading this cookbook and cooked out of it, I kept seeing strong similarities between Thai and Laos food. How did Lao morph into Thai?

James: My theory, it's the way we found was tracing back through immigration. People always ... a culture will always ... when they move the thing they take with them, not in their suitcase or whatever, is the food they eat. The food they love. The food they comfort with. That's their security blanket, their food, this nourishment. So, when Bangkok was bustling as the big city that was the land of opportunity. A lot of people from Isan migrated to Bangkok to become your cab drivers, you construction workers, your maid, and your blue collar workers.

Obviously they brought their food with them. The ingredients were all there, we shared the same ingredients. But it was the style of cookery was much different than the city. So they would start cooking a lot of these foods for themselves. To feed themselves among their own community. Then it kind of caught on by the people who lived in Thailand centrally and in the city, like wow we are not used to these flavors. It's different.

There it existed in Thailand and Isan is part of Thailand, Nationally. So there's no fault to calling it Thai. I think it's both correct. It's Thai and it's Lao. It's not one or the other.

Suzy Chase: As a tenth grader you thought to yourself "I need to do this." after you saw a story about the French laundry. Then you were off and running. Tell us about culinary school.

James: Yeah in tenth grade I already knew what I wanted to do. I was in advance placement classes, the college preparatory classes, more reading, reading Charles Dickens and scarlet letter. Asking myself, I want to be a cook. All these SATs SATs wasn't going to help me. That didn't call or sing to me, what sang to me was like gourmet magazines and Art Culinaire and the French Laundry Cookbook. That's what kept my interest. That's what I wanted to read and wanted to do.

So yeah, I kind of bowed out of my AP classes. I figured I needed to get on a fast track, start planning, getting ahead. I need to be in kitchens where all the stuff I read could actually be piratical.

I know that just from working at my mom's restaurant since I was a child. I had great knife skills and all that, but I never had the chance to really cook with butter, or cream, or make beurre blanc and work with foie gras or ya know instances of butchery of different animals. I never had to do that in my mom's kitchens. That's what I needed to learn and grasp, that's what interest me so I had to set myself up and plan to get there. To get these experiences and seek them out and make it happen.

Suzy Chase: Then in 2009 your fine dining restaurant Commis earned a Michelin star in less than four months of being opened. Talk about that!

James: Yeah so my first restaurant was in 2009, we opened Commis first, of all things. I love fine dining, I still do. I love the artistry of it. I love the production value of it. I love the discipline of fine dinning. I think that's the thing that comes across. No matter of level of cookery, rustic or not, there's a fair amount of respect and discipline because it is a craft on every level.

So yeah, we opened that and we got the Michelin star and it felt good, it felt good to be home in Oakland. After traveling and working elsewhere and to be grounded back home again. And having this responsibility now that a Michelin star. That's like worldly, globally recognized. That was definitely an honor and like I said responsibility. It was a good time to exhale a little and like okay we did it! It was just fantastic.

But what does this all mean? The restaurant got busier, thank God. Yeah it was kind of like, that's Commis. And then we're about eight years old now. It's been a good ride, and it gets better by the day. I still love the restaurant every time I go in. It still feels fresh and brand new.

Suzy Chase: So then at one point in the book, after your stint in Europe, when you realized you wanted to open Hawker Fare the restaurant you wrote "The dishes I was raised on, everything I love most, I had no idea how to cook." How did you tackle that?

James: Yeah I was like who was going to cook all these things for me? All these chili dips she used to give to me all the time in the refrigerator. It's kind of a shame I grew up on this, I was in the kitchen when she made these things, but I don't know how to do it. I kind of skipped or turned a blind eye on like an opportunity of educating myself how to do this. So I had to dust off the cobwebs of my taste buds and remember what things taste like and kind of use my fine dining pallet and skill to figure it out on my own. And really trust my own pallet and my own memory and what things were supposed to be or taste like. Of course, I have mom to sign off on it. But I needed to trust myself first. Like, oh does this jog memory. There's just this ... does this take me back to ... does this chili dip take me back to 1989 when I first had it.

Suzy Chase: Wow.

James: So that was my gauge of learning myself how to cook this food. I did it with a lot of trial and error, it wasn't easy. But I think that my training in fine dining definitely helps, like training my pallet. Kind of gives me the tools to build my map how to get to where I need to be with a specific dish. This was like, mom's food, where there's no scales. It's a handful of this, a handful of that. Lots of love. That's all it needs and requires. Sometimes you know, am I over thinking this? It's like oh I think the ratio of sugar to fish sauce is two to one and there's like, we don't know. Let's just make it taste correct and worry about the ratio and write down the recipe later. It's kind of like building a recipe through numbers rather than as we go tasting. It's kind of like to taste. It was a different way of approaching a recipe.

Suzy Chase: I found it interesting that the recipe measurements in the cook books included grams. Why did you do that?

James: I wanted it for the reader to say, if you needed to adjust the recipe like double it or triple it, or doing it in half. It's much easier in grams, than trying to measure out. It's easier to measure out a recipe that says ten grams and just measure five if you want to cut the recipe in half. Rather than do a half teaspoon then do that's a quarter teaspoon. I don't have a quarter teaspoon measure. Just doing metrics just makes more sense in cooking in general. I think it gets you to a better product, and the funny thing is that's not how this food's made.

So I'm kind of, a way for me, I'm trapped between two worlds, and both are correct.

Suzy Chase: On parts unknown, Anthony Bourdain mentioned that it was only your second time back in Laos. Did you have that familiar feeling of home when you went there, or did it feel totally foreign to you?

James: Definitely had a flashback of my youth, of like our living room and our interior house to some of these houses and villages. It's very reminiscent of the way it's decorated and everything. The way things are placed, it feels like home. That was kind of weird also, like noises and no one spoke loud in the household. So that was very nostalgic to me, that was very ... but being overwhelmed with it. That was different, it was kind of like everywhere. It's like, this is the way of life. It's not just where our house was just, oh we're different cause we're different. No, this is who we are. And that was very eye opening and comforting in a way.

Suzy Chase: Last weekend I made your recipe for poached chicken with rice, Khao Mun Gai on page 181. Is that how you pronounce it?

James: Correct.

Suzy Chase: Okay, good! This is the most delicious broth I have ever tasted in my entire life and I'm actually making it again right now. It's on my stove as we speak. Can you describe this heavenly dish?

James: It's a one pot dish, humble, you get this whole chicken either from your yard. That's how we would do it from home. And then you make this beautiful stock, with aromatics, then you take the chicken out. You kind of let it sit to room temp when it's fully cooked and moist. You always got to cook it to the bone, makes it more succulent. Then you have this beautiful broth, you can serve by itself. But you take that broth, there's so much of it, cause you need enough to submerge the chicken to poach it in.

Suzy Chase: A gallon of water.

James: Yeah. So you cook that with the rice and then it's one of those dishes that kind of connect the dots. You know you have everything from the broth, you're eating the entire process of this dish minus the sauce, obviously. It's just a very comforting thing, like something ... one of those things you when you feel homesick, want to eat every day. For me it would be like Khao Mun Gai. That's like you know rainy day, nice day on a picnic, when you're sick. It's the equivalent of chicken noodle soup.

Suzy Chase: Oh but like twenty million times better.

James: Thank you.

Suzy Chase: So what's the deal with pink chicken? I always thought that pink chicken was undercooked but in the book you say that's not so.

James: Yeah I think it's more of a cultural difference. For me even today, you go to China town you get like a soy sauce chicken, whatever, they chop it up on the cutting board it's bleeding. We're there to cook the meat, but not the bone marrow. Once you cook the bone marrow to where the point it's brown, the chicken's overcooked. It's no longer enjoyable. It's not juicy, it's not succulent. I think that's where it comes from, it's more like a cultural ... a lot if it's like a cultural difference than what we're used to here.

Suzy Chase: Where can we find you on the web, social media, and where can we find your restaurants?

James: Well my restaurants in Oakland, Commis in Oakland, Hawker Fare is in San Francisco. You can find me on social media at James Syhabout all lower case first and last name put together on Instagram, Twitter.

Suzy Chase: You have opened up a whole new world of food for us. Thanks James for coming on Cookery by the Book podcast.

James: Thank you very much for having me, it was a fun discussion. Thank you.

Suzy Chase: Follow me on Instagram at Cookery by the Book, Twitter is @IamSuzyChase and download your Kitchen Mix Tapes, music to cook by on Spotify at Cookery by the Book. And always subscribe on Apple Podcasts.