Grist | Abra Berens

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Intro: Welcome to the number one cookbook podcast, Cookery by the Book with Suzy Chase. She's just a home cook in New York City, sitting at her dining room table, talking to cookbook authors.

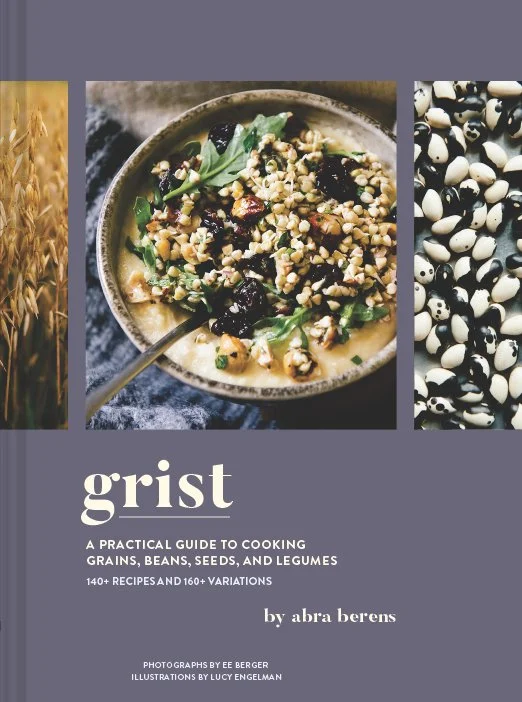

Abra Berens: My name is Abra Berens and my most recent cookbook is called Grist: A Practical Guide to Cooking Beans, Grains, Seeds, and Legumes.

Suzy Chase: Before diving into this book, I'd like to thank my new sponsor, Bloomist. Bloomist creates and curates simple, sustainable products that inspire you to design a calm natural refuge at home. I'm excited to announce they've just introduced a new tabletop and kitchen collection that's truly stunning. Surround yourself with beautiful elements of nature when you're cooking dining and entertaining and make nature home. Visit bloomist.com and use the code "cookery20" to get 20% off your first purchase, or click the link in the show notes. Now, on with the show.

Suzy Chase: You wrote in Grist. "Rarely am I enticed by a recipe and then seek out the things I need to make it." That kind of blew my mind and I would love to hear more about that.

Abra Berens: Well, first of all, thanks so much for having me back. We're avid podcast listeners in our kitchen and Cookery by the Book every week, it's one of the faves, and so it's a real treat to be back. But yeah, so I'm not much of a recipe follower, and so that's, I think, probably part of it, but it's also just the thing that makes me want to cook are different ingredients.

Abra Berens: Oftentimes, at least with grains and legumes, I have a wall in my kitchen that has a bunch of jars sitting in kind of shallow shelves and a bunch of jars with these pulses in them, and oftentimes dinner will be kind of like, "Okay, this is what's in my fridge," and I'll look at the wall and be like, "Oh, I do have those black lentils. Sounds good. I'll cook those up," that sort of thing. It's rare for me to flip through either a website or a magazine and say, "Oh, that sounds really good. I'm going to buy all of those things," and then schedule a time to make that thing in my kitchen. I'm just not that good of a planner, and so yeah, that's kind of how it works, and it ends up being really focused on the ingredients as the enticing factor, if that makes sense.

Suzy Chase: Ruffage was about your experience growing the vegetables and Grist is all about things you haven't grown. Can you talk a little bit about gathering farmers' and growers' stories for this cookbook?

Abra Berens: Yeah, that was one of the first nuts to crack for this book for me was that I wanted Ruffage to contextualize these ingredients, mostly to mirror my own understanding of them that came about through growing them. I really loved the storytelling that was in Ruffage and I was struggling with, "How are we going to do that for this book?" I've got a couple of things about in the corn chapter, there's a story about words and how "polenta" gets used instead of "cornmeal mush," which is the older Midwestern term for polenta, and so there were a couple of stories like that.

Abra Berens: But then I thought, "What's really missing is this sense of how these ingredients are grown," and then it dawned on me: It's because I don't grow them, none of us really do, because it doesn't make sense if you grow all be your raised beds in even the biggest garden, by the time you get the wheat berries out and mill it, you'd have like a cup of flour, and so I was like, "Well, how are we going to tell these farmer stories? Or how do we contextualize this and bring to light some of these invisible jobs?" Then it occurred to me: "Just ask them." Thankfully, I live in rural Michigan. One of the people who's profiled is my cousin, Matt, who's an edible bean grower, so that's really where it started, was wanting to talk to him about what his farm cycle is like.

Abra Berens: Then also, Michigan is the second most agriculturally diverse state in the nation. That means we have a lot of growers, and so it occurred to me that farmers are not a monolith. How do we showcase the different experiences that different farmers have? There is a woman, an amazing woman in Detroit, Jerry Hebron, who owns Oakland Avenue Farm, and she is also growing effectively beans in Michigan, but she's growing crowder peas, which are a field legume, and she's growing them in the center of Detroit and growing them for her community as a tool to achieve some of the things to help resolve some of the inequities she sees in her community of lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables and beans, in this case, community engagement, providing employment opportunities for people who struggle to find traditional jobs and job training skills, things like that, and I was like, "These two farms are vastly different, but they're both growing beans in Michigan, and that feels really important to understand."

Suzy Chase: Yes, Jerry Hebron was one of my favorite interviews in the cookbook. I think that conversation really brought to light the difference between urban and rural growers and I feel like urban farms rely heavily on community involvement.

Abra Berens: Yeah. I think the intention is a hundred percent different and that's not to say one is better than the other, one is right, one is wrong. They're both using food to solve different problems. I agree, I think that that conversation is such a valuable one because it showcases people who will say, "Well, food is political," or, "Food brings people together." Well, those are all sort of hollow statements until you really get into why. I think someone like Kim Severson from The New York Times always says, "Every story has a food angle," and it's because food touches absolutely everything in our society. It touches inequality, labor practices, immigration policy, economics, both on the macro and micro level, just absolutely everything, and so it really is a valuable tool to both assess some of these issues and also to fix some of them, so I think it's a really important thing to understand what the successes and hurdles of these growers are across the spectrum.

Suzy Chase: In the cookbook, you talk about how grains and legumes are perfect candidates for batch cooking, but the idea of eating lentil soup for the next few days is daunting, so you have some interesting tips to avoid that in your variation section, which I love.

Abra Berens: Thanks. Yeah, I was thinking a lot about batch cooking with this for a couple of reasons. One, there happened to be on Twitter, I witnessed a thread that was pro batch cookers versus anti batch cookers, which is a funny set of camps to have evolve. Basically, somebody's saying, "I never batch cook anything because it's so boring and it always goes to waste."

Abra Berens: It occurred to me that restaurants batch cook, but no one thinks of it as batch cooking. It's prepping, it's bringing ingredients to 80% of ready, and then finishing what they're going to become in the moment when something is ordered. I'm constantly trying to find ways to bring a chef or restaurant mentality to people in their kitchens. It's difficult, but it's also, it's kind of like figuring out those nuggets that work for folks, and so for me, it kind of dawned on me when my sister made, I think, like two gallons of lentil soup and then was eating it every day and just bemoaning it, and it occurred to me that if she had cooked off some lentils, then she could have a number of different meals and not worry so much about the monotony of it and could have ended that week with lentil soup, and so just thinking about it in a slightly different way. That's what those variations are, it's how to take something, cook it really simply to start, and then different suggested ideas for how it could show up throughout your week.

Suzy Chase: Grist is a comprehensive guide through 29 different grains and legumes. You give credit to where the grain originated. The word "grist," the title of this cookbook, I had never heard before. Can you talk about the word "grist"?

Abra Berens: I almost hesitated to use it because it's the act of milling something. In a lot of towns, they would have a grist mill, and so I always knew it as that, as an adjective for a community mill. What I liked about it is that it was indicative of how a lot of these ingredients are used. It also has a colloquial side of something to chew on or something to think about, which I found this book to be really heavy on as I was writing it. I mean, it was much more research for me and much more learning for me than with Ruffage.

Abra Berens: Ruffage was like, "Here's this topic that I feel like I know a good deal about and I want to convey that," and with Grist, it was like, "What is the legacy of wheat? Why are there so many different variables to this?" Or, "I massively overcooked buckwheat the first time I made it because I just assumed that it would take an hour to cook because it has a hard reputation," and so I was really learning along the way, so it was grist from my own mill of thinking about these things.

Abra Berens: Then I think, truth be told, I really wanted to call the book either Fodder or Silage to continue this sort of tongue-in-cheek joke of something that doesn't sound good, but is actually good. Eating whole grains, I feel like people are always rolling their eyes at, and the much wiser folks at Chronicle said, "Absolutely not. We're not using those titles," and so this was our happy medium.

Suzy Chase: You also highlight invisible jobs like your seed cleaner, Carl Wagner, who you work with at Granor Farms.

Abra Berens: Yeah, that was the other thing that I found so fascinating about this book. Again, tied to the pandemic and all of a sudden, all of these essential jobs that people maybe didn't think that much about before we deemed them essential. Carl is a good friend of our farm and I didn't know that his job even existed until I was working here. What his job is is to get a bag of flour, the farmer has to plant the seed, grow it, and then harvest it, and those long amber waves of grain go through a combine and the combine cuts them down, separates the wheat berries from the rest of the plant, and then stores those wheat berries and gets them into a storage bin. Then it goes to a mill, but there's this seed-cleaning process that has to happen. That's because the wheat berries still have a lot of debris in them and there's also a good amount of damage that can come just from that harvesting.

Abra Berens: What Carl does is he takes, think of them like air hockey tables, and passes the seed through these varieties of screens and air hockey tables in order to separate out the good seed from, I guess, the bad, which could be anything from cracked and broken ones are going to be lighter than the whole seed, and so when they pass through the air tables will blow off the top, or they are lighter than rocks and stones, which are easy to get into the mix, and so the rocks and stones sit and the wheat seed bubbles up. Then when it passes through screens, all of these seeds have specific sizes, and if there's, say, weed seed, or if, say, that field had corn growing in it the year before, you might get some stray corn in the mix, and then that's going to be so much bigger than a wheat berry, and so it won't be able to pass through the screen. It's this very specific job that is highly skilled, that I don't think anybody really knows that much about.

Abra Berens: Carl, I think, is a really fascinating character because I'm also so curious how we're having major issues with succession for farmers and what happens to these farms if their children don't want to take them over. I think he's a fourth-generation farmer. I can't remember off the top of my head, but he was confronted with this idea of, "I live on this family farm and I want to keep farming. What is my path going to be to continue to be a part of this farming community?" He is an agronomist by trade, but then decided, got really interested in seed cleaning and seed saving and seed stock, and so that's where he has added that to his family's business. I just think he's an example of an incredibly smart, incredibly specialized skills, talented person that I don't think as consumers we hear that much about that often.

Suzy Chase: How was that first meeting with him? Were you like, "Carl, I didn't even know you existed"?

Abra Berens: Yeah. Thankfully, I had met him before I had to interview him. Wesley Rieth is the grain grower at Granor, or he manages that program, and so he knew Carl and had developed a relationship with him, so I think to piggyback on that relationship, but yeah, I mean, it was that, I basically was like, "I don't know anything about this, and so tell me about it." Maybe I just think that's a valuable thing in life, to be able to say, "I don't know anything about this, but I'm really curious, so I want to learn about it," and I think that just kind of sums up curiosity and food as a whole.

Suzy Chase: The look and feel of this book is so similar to Ruffage. Did you work with the same team this time?

Abra Berens: I did. That, I think, is one of the greatest things is that I knew that I wanted this book to be a sibling book to Ruffage, but then it was kind of twofold the positives, one of which was that everybody who worked on Ruffage came back and wanted to work on this one again, so same photographer, same stylist, same illustrator, same design team, same editorial team, all of that stuff. That's really meaningful to me because it means that people felt like their work was well-represented and that they enjoyed working on the project. They felt like it was worthwhile. But then also, it gave us the ability to just get better at what we do. Ruffage was my first cookbook. I don't work in food media. I've never ghostwritten a cookbook. I had done like one photoshoot, I think it was for Quaker Oats, beforehand, and so I had really no idea how to do this and was so reliant on instincts and guidance from other people.

Abra Berens: The best example that I have for this, about how we came to this project in a new spot from our experience with Ruffage was that the photography team, Emily Berger and Molly Hayward, they were really proud of the photos in Ruffage, but they didn't love the chapter headers. They didn't feel cohesive to them, they felt a little bit happenstance, and so they came to the shoots with this idea of how to do the chapter headers differently, so we shot all of the chapter headers one after another in one day in June. Molly just took these things that are not inherently super-differentiated, wheat berries versus oats versus buckwheat, I mean, they all kind of look the same, and she did an amazing job of figuring out how to lay them out and style them so that they look engaging and different and really showcase how each of these grains looks.

Abra Berens: Then similarly, Lucy Engelman is the illustrator, and I didn't really know exactly what to ask her for with Ruffage, and so a lot of her illustrations end up being little doodles in the margins. She's such a talented, detailed infographic specialist, so I was like, "Okay, these doodles are great. They also don't serve that much of a purpose and we have limited page numbers, so let's really leverage Lucy's skill to convey a lot of information in a short page length," and so she did these amazing infographics that explain very complex issues beautifully and on a page or two. I'm so proud of all of the work and all of the ideas that everybody brought to the table. You can't ask for anything better, really.

Suzy Chase: It's November, and for last night's dinner, I turned to your stewed chapter. I love stews more than soups. The stewed section walks us through 12 easy steps to get dinner on the table. My base was onion, sweet potato, and vegetable stock on top of some leftover rice and peas I already had. Can you talk a little bit about the process?

Abra Berens: As I was thinking about this book, one of the other things I came up against is how do these ingredients, which are often very interchangeable, how do we differentiate them, but also how do we just show that they're similar and that you can apply the same preparation techniques to most of them? That was the starting point for the technique portion and there's boiled, stewed, fried, flour in most of the chapters, and then it was like, "Well, a lot of these techniques are really similar, and so how do we show that people don't have to follow an exact recipe, but have these basic elements?"

Abra Berens: The grid that you're talking about is my distillation of that, of if I'm going to take an ingredient and stew it with other flavors so that those flavors are represented in the final dish, what are the steps that I go through no matter what the ingredients are? It's often starting with an aromatic base, it is adding a liquid to it, finishing it, maybe with something crunchy, finishing it with something bright and acidic to really lift those flavors, and then to give a bunch of options so that people can hopefully see how to mix and match some of these building blocks to get something different or to use up something that's in their kitchen already.

Suzy Chase: You have an herb relish and flavorful rig chapter to top your stew, so I use the garlic breadcrumbs, and I was wondering, "What is a rig?"

Abra Berens: It's a made-up word. Yeah, it's funny, this is the other thing that happens is restaurant kitchens develop their own language. I realized my friend Erin and I, who cook together professionally, we often are making these chunky, acidic relies, but "relish" kind of connotates what goes on a hot dog or something like that, or cranberry relish, and so "relish" wasn't quite the right word. She always just used this word "rig," like, "We're going to rig it up," and so I started using the word "rig." Then maybe five years later, I was like, "What does that mean to you?"

Abra Berens: We defined it in the glossary. She said, "It's something on the lines of an indescribable, chunky, acidic condiment that blah, blah, blah." It's really just a catchall for these kind of weird condiments that we use a lot, which are not condiments like ketchup, but condiments like herb relishes, or adding toasted walnuts and parsley and lemon and olive oil and a little bit of shallot makes this really flavorful thing that adds a hit of brightness, a hit of texture, maybe a hit of salt to whatever you're finishing. Most of these grains and legumes, if you think about a spectrum of flavors, they're really a lot of base notes. They tend to fill the hearty warming anchor of a meal and that can get kind of dull if it doesn't have something punchy paired with it, and so the condiment section is really my most recent collection of ingredients and condiments that we're using to punch things up.

Suzy Chase: I'm thinking the word "rig" totally works.

Abra Berens: I think it does, too. Somebody said, "Oh, it's like jimmy-rigging a situation when you've got a half-broken whatever and you're just making it work." I was like, "Yeah, that is kind of how it is." It's just this thing that sort of ties everything together, but is also, it doesn't have specific parameters. I feel like when you get into something like a pesto or these things that have actual names, then you're kind of beholden to those recipes, and this is a little bit freer.

Suzy Chase: Now, to my segment called Dream Dinner Party, where I ask you who you most want to invite to your dream dinner party and why, and for this segment, it can only be one person.

Abra Berens: I would love to have a dinner party with Earl Butz, who was Nixon's secretary of agriculture and who I think spearheaded a lot of the agricultural policy that is problematic and is playing out problematically in our system, and just to be like, "You're crazy. Don't do this." I don't know. Maybe I got a different answer, Suzy. I don't know if we can just like-

Suzy Chase: I did not see that one coming.

Abra Berens: ... Yeah, I didn't really, either. It's not... I mean, it's-

Suzy Chase: I love it.

Abra Berens: ... It's a super nerdy answer.

Suzy Chase: Well, I love it because you want to talk to him about maybe changing his ideas for the future. So many people answer this with like, "I just want to talk to them and blah, blah, blah," but you have an agenda for your dream dinner party, and I love it.

Abra Berens: Yeah, I guess that's the secret. If I ever invite you over for dinner, there's a secret motivation. But no, I mean, I think it's true. I think that we're still navigating a lot of those things and I guess maybe I'd like to hear from him why he thought these things were good ideas because nobody behaves sinisterly just for the sake of being sinister, but I do think it's caused a lot of problems that we have to reconfigure.

Suzy Chase: Where can we find you on the web and social media?

Abra Berens: All of my social media is @abraberens, which is my first and last name, and outside of that, Grist is available at a ton of independent bookstores across the country, as well as the big boys like Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

Suzy Chase: To purchase Grist and support the podcast, head on over to cookerybythebook.com. Thank you so much, Abra, for coming back on Cookery by the Book Podcast.

Abra Berens: Suzy, well, thanks for your time, and for all that you do to create a space for authors to talk about their work. It's really valuable. Thank you.

Outro: Follow Cookery by the Book on Instagram, and thanks for listening to the number one cookbook podcast, Cookery by the Book.